I have 20 or so direct ancestors who were Confederate soldiers. In my research, I discovered that 11 served in Texas units, 2 served from Mississippi, 3 from Alabama and 1 from Arkansas. Clearly, the Western theater was well represented in my ancestry! That made me interested in researching what their wives, daughters and sweethearts would have worn... because everyone knows that the ladies "out West" dressed differently than those "back East," right?

Well... not so fast.

When investigating the clothing of a particular region, it's always helpful to look at four things:

- Diaries and memoirs from people in that region

- Photographs of people in that region

- Original clothing from that region

- Documentation of shipping imports and shop stock from that region

I decided to look at these categories and blog about them. But don't worry, I also decided to break this up into several blog posts because each of these topics can be pretty big! The diaries and memoirs were the most fun for me, so I'm going to start with them. Since I'm looking specifically at war-time related fashion in the Confederacy, I decided to focus on just the Trans-Misssissippi area. I've categorized these books by Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana and Texas. And yep, there are a lot more than these, but I narrowed it down to these because I didn't want my blog post to become gargantuanly long! (Did I just invent a word?)

So here we go...

So here we go...

Mississippi

Brokenburn: The Journal of Kate Stone 1861-1868

The Journal of Kate Stone, from Mississippi, is free online. She has a number of great sections concerning clothing and fabric. Here are some quotes to enjoy."Mamma had several of the women from the quarter sewing. Nothing to be done in the fields too muddy. They put in and finished quilting a comfort made of two of my cashmere dresses. Mamma had Aunt Laura's silk one put in today and Sue is quilting on it.....This will be a lovely silk affair. Aunt Laura always has so many pretty silks and wears them such a little while that they are never soiled." Silk and wool were obviously available and had been for some time if they had worn-out dresses of those fabrics to be used in quilts!

Later on she talks about cutting up old dresses to make clothing for the soldiers. "And I have not a thing that will do. We have cut up every silk and wool thing we have for the different boys."

When some marauders stole their goods, she made an interesting itemization. "Now for a list of our losses. All the clothes left in the cart were taken by Mr. Catlin's Negroes, Uncle Bob being unable to protect them. They comprised most of our underclothes and dresses, all my fine and pretty things, laces, etc., except one silk dress, all our likenesses, and all the little family treasures that we valued greatly." In spite of the thieves' action, she apparently still had at least one silk dress left.

Of course, buying nice fabric became hard as the blockade took effect and all textile mills were working largely for the army's needs. But good fabric was still available, though expensive. "I must confess, on getting home, Mamma did not like a thing I bought, and most will be returned if possible and the rest kept under protest. I am a poor shopper and must have execrable taste. The $95 dress I bought Mamma is ugly. But it was the only piece of woolen goods in town, and Mamma has nothing warm for winter."

Obviously silk and wool were not only available, but considered first choice for women's clothing. Was cotton mentioned? Yes, we find references to "calico," a type of cotton, here and there. "This evening we rode down in a light shower to see how Mrs. McRae and Bettie were getting on, Mamma in a riding skirt of rags and tatters and I in a calico dress and the remains of my old green habit." Calico here was not a fashionable choice, but apparently worn for a dirty ride in the rain.

"Everything has gone up in the same ratio. We expect to suffer for clothes this winter. We hear of a gentleman offering $50 for a pair of boots and then waiting for weeks to get them made. Unless we capture some Northern city well stocked, there will soon be no dry goods in the Confederacy. The ladies are raising a cry for calicoes and silks that echoes from the Potomac to the Gulf." Apparently calico was just as hard to get as silk, thus refuting the claim that cotton was the cheap alternative to silk. She mentions later, "There are several well-filled stores, but the prices are beyond anything.

We saw a pretty light calico but Mamma could not afford it at $6 a yard."

Alabama

Fannie Beers' Civil War

Fannie Beers' "Memories" is another memoir of a Western woman and is also free online. She married a man from Alabama and traveled quite a bit during the war. But she eventually wound up as matron-in-charge of the Second Alabama Hospital. Her memories are fascinating.When I came through the lines I was refused permission to bring any baggage ; therefore my supply of clothing was exceedingly small. I had, however, some gold concealed about my person, and fortunately procured with it a plain wardrobe. This I had carefully treasured, but now it was rapidly diminishing. At least I must have one new dress. It was bought, a simple calico, and not of extra quality. The cost was three hundred dollars! With the exception of a plain muslin bought the following summer for three hundred and fifty dollars, it was my only indulgence in the extravagance of dress during the whole war. Two pretty gray homespuns made in Alabama were my standbys.

Though the cotton calico fabric was expensive, it was apparently still considered "simple" and "not of extra quality." Even her "homespuns" (which could have been cotton, wool, or a blend of the two) appeared to have been preferable. We can infer that wool and silk would still have been the favored choice.

A Blockaded Family

A Blockaded Family: Life in Southern Alabama During the Civil War by Parthenia Antoinette Hague is another fun reminiscence. Parthenia and her friends, like most young ladies of the 1860s, knew very little about spinning and weaving homespun fabric. The war changed all that."While knitting around the fireside one night, talking of what we had done, and could yet accomplish, in industries called into existence by the war and blockade, we agreed then and there that each of us four could and would card and spin enough warp and woof to weave a dress apiece. This proved a herculean task for us, for at that time we barely knew how to card and spin. Mrs. G smiled incredulously, we thought, but kindly promised to have the dresses dyed and woven, in case we should card and spin them."

The story of how they learned the intricacies of spinning thread, weaving material and then dyeing it for use (or dyeing the thread first) is very interesting and entertaining. They were quite proud of their patriotic homespun dresses!

However, the preferred material for dresses continued to be the old favorites, wool and silk. The stories of their efforts to produce those fabrics is also quite interesting.

"Some very rich-appearing and serviceable winter woolen dresses were made of the wool of white and brown sheep mixed, carded, spun and woven just so; then long chains of coarser spun wool thread dyed black and red were crocheted and braided in neat designs on the skirt, sleeves, and

waist of these brown and white mixed dresses of wool."

The need for Southern-produced wool was recognized early in the war and quickly remedied by ranchers raising more sheep and textile mills working the wool into fabric. The Austin (Texas) State Gazatte noted on May 25, 1864 that, "Great enterprise is being shown in the erection of powder mills, cotton and woolen factories, &c. To employ the latter there has been secured, on Government account in Texas, one million pounds of wool."

But wool fabric was also produced in homes for personal use.

|

| An Alabama homespun dress |

Imported silk was not always easy to get but all ladies of the Victorian era knew how to save and reuse old dresses. Here's a really engaging account of how one lady did it.

"A woman who was a neighbor of ours made herself what really was an elegant dress for the times. The material was an old and well-worn black silk dress, altogether past renovating, and fine white lint cotton. The silk was all ripped up, and cut into narrow strips, which were all raveled and then mixed with the lint cotton and passed through the cotton cards two or three times, so as to have the mixture homogeneous. It was then carded and spun very fine, great pains being taken in the spinning to have no unevenness in the threads. Our neighbor managed to get for the warp of her mixed silk and cotton dress a bunch of number twelve thread, from cotton mills in Columbus, Georgia, fifty miles from our settlement, and generally a three days' trip. She dyed the thread, which was very fine and smooth, with the barks of the sweet-gum and maple trees, which made a beautiful gray. Woven into cloth, it was soft and silky to the touch, and of a beautiful color. It was corded with the best pieces of the worn silk, and trimmed with pasteboard buttons covered with some of the same silk."

Louisiana

Celine

Celine: Remembering Louisiana 1850-1871 is an engrossing read but be prepared to flinch at her descriptions of life as refugees in the war. In addition to life-threatening concerns such as avoiding battling soldiers and finding enough food to eat (not to mention shelter), Celine also addresses their struggles with clothing. Nice clothing was still available for many, as evidenced by this comment."Later some of the neighbors called – Mrs. Wiley, Mrs. Cross, Miss Perry, etc. All were pretty women and were dressed in silk dresses protected by aprons, small, fancy aprons. Grown people’s nice clothes lasted pretty well the four years. With children it was different, we grew out of them."

But this heartbreaking description not only shows how hard it was to dress well, but also what they felt were absolute necessities for dress - things like silk dresses and coverings for their heads.

"In jumping out of the wagon my dress caught on a splinter and was badly torn. It was a black silk of Grandma’s trimmed in narrow strips of blue, the leavings of the blue stripes which had been inserted in the Creole Guard’s flag to change it after the secession. The old dress had done its time and more, but I felt very sore on walking down the cabin of the boat with my clothes in tatters.

"There were on board several ladies and a young girl of my age. They were all very well dressed. I felt awfully poor and 'backwood' in their presence. Although we had never thought of our attire in Jackson where everybody looked the worse for wear it came on me like a thousand stings; the figure we must have cut to people who had not suffered want or had had time and opportunity to recuperate. As we walked in the boat here is our picture or description. Ma wore a grey, glazed cambric dress with trimming bands of Persian design calico and a new bonnet she had just had sent from Baton Rouge. The bonnet was green straw trimmed in green moire ribbon. She had on a beautiful lace mantle fastened on the shoulders with gold pins. Those kind of garments, not being worn during the war, were nice and fresh as when she wore them last in 1861. Her shoes fitted her well. They were of brown velvet with leather soles of the top of a Yankee knapsack.

"Sister and I had on those black and blue silk dresses, at least four or five inches too short, and mine in tatters. Sister had no shoes on at all. Mine were heavy ones 'Uncle' Tom had made. My stockings were homespun, home knitted ones, more or less soiled by the dust and grime of our fifteen mile drive. Our hats? Well, they had been of pearl grey straw at Easter of 1861 and had had dainty pink sprays of arbutus as decorations, but the rims had become so nipped. They had gotten so sunburned that they were of a mottled, faded, orange hue. I had cut the rim down and bound them with faded Scotch plaid ribbon and an apology of rosette of the same ribbon ornamented the crown. They were simply better then being bare headed, that was all."

Texas

A Rebel Wife in Texas: The Diary and Letters of Elizabeth Scott Neblett 1852-1864

A native Texan, Elizabeth's letters give us a detailed and informative look at life for Texas women in wartime.

As these prices show, cotton calico was not the cheapest option available. Homespun wool fabric was apparently even cheaper. "I wish you had got me a calico dress like Oliver got for Mrs O, gave $50 tis good calico & dark enough. He sent it by Warren. I have no hopes now of getting a dress. Dr Kerr has calico in town selling for $10 per yard, but I live in the woods where no body will see me, & if I can only get my home spun wool I’ll be fixed. In haste. yours affectionately, Lizzie."

As these prices show, cotton calico was not the cheapest option available. Homespun wool fabric was apparently even cheaper. "I wish you had got me a calico dress like Oliver got for Mrs O, gave $50 tis good calico & dark enough. He sent it by Warren. I have no hopes now of getting a dress. Dr Kerr has calico in town selling for $10 per yard, but I live in the woods where no body will see me, & if I can only get my home spun wool I’ll be fixed. In haste. yours affectionately, Lizzie."

Fashionable standards for clothing and manners were apparently still considered necessary by many Texas women, including this women of ill repute. "I also changed my boarding house a day or two since. I have been suspecting that the young widow was not all right from what I had seen of & several men who came there, but a few days ago a woman splendidly dressed in black silk and fine jewelry with a young girl about 16 took dinner there. They left the table before the rest did to go to the depot and some of us asked the question who they were, and were informed that one was Mrs Hawkerson and the other – I cannot recollect her name. Mrs H is a woman famous in Galveston for keeping a sort of private aristocratic whore house a short distance out town. I was surprised at this discovery and particularly at the elegance of her manners and it at once made up my mind to quit the place."

Elizabeth's own standard of "proper apparel" was so firm that she even refused to go out publicly without it. "I know how bad it is, to desire to go into company and forced to stay at home for the want of proper apparel. I never desire much to have fine dressing, yet still I have stinted myself woefully all my life….If I could recall the past I would act differently. I would spend a little more on my self than I did. But that is past, and if I haven’t a black silk to be buried in I have a white dress which will look well enough for me."

Letters From the South Texas Frontier

A large German community helped build Texas during its frontier days and Maria von Blucher was one of these German transplants. All through the hard pioneer life of poverty, sickness, war and violence, she maintained her standards of decency in manners and clothing. These letters home to her German parents are a fascinating look at her constant efforts to raise her children with proper manners, education... and clothing.

In spring 1860, Maria joyfully wrote to her parents about buying a Wheeler & Wilson sewing machine and enthused about how much time it would save her in sewing.

By 1862, the wartime depression and blockade, as well as Corpus Christi's shallow harbor which didn't allow serious shipping, had seriously affected the family's ability to dress well. "Times are hard for all families. Clothing cannot be bought at all, except if anyone is fortunate enough to be able to send silver to Mexico to get some....There are no shoes at all, and it was good fortune that I had two hides of good leather from which I myself make shoes for our family....I have resolved to wear out all my dresses before giving $26 for plain white calico to make dresses for myself and the girls. Calico now costs $1 a yard."

In spite of their struggle to buy decent decent clothing, she mentions in December that a friend "brought along gowns for the girls from Mexico."

In 1863, she received some cash from her parents and used it to purchase a number of items including "shoes, shirting, sole leather, one length of cotton, and one piece of colored skirting, so that I am now provisioned for some time."

When her parents sent some fabric later in the year she reported, "Our black woman is still with us, all gracious energy in running and ruling the household. I made her a present of colored fabric that many a lady her would be pleased to have. Having received all the fine things from your crates, I did not want to leave her empty-handed."

Even as late as November 1864, she apparently still had nice silk clothing on hand that she could sell to maintain her family through severe drought. "I had to sell my fine green silk dress and the wonderfully fine table cloth you had sent me, and likewise many other things. The green dress was as fabulous as my wedding dress, and I struggled over parting with it. Yet what is gone is gone and it is no use feeling sad about it."

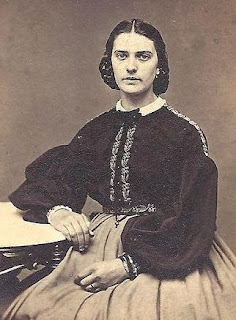

|

| An unidentified Texas lady |

CONCLUSION

It's clear that Southern ladies in the West suffered from wartime shortages and the blockade, just as Eastern ladies did. However, it's apparent that their standards for dress were generally the same as Eastern ladies. Silk and wool were the preferred fabrics. Cotton was not a cheap substitute, since obtaining it included the necessity of spinning, weaving and dyeing it themselves (unless they were able to get an expensive, imported bolt through the blockade).Farm women in the East and ranch women in the West both made allowances for dirty outdoor chores. Bare feet, pinning up or shortening their skirts, and even dropping their hoops happened by necessity. But ladies of nearly all social strata, East and West, felt that going out into public required higher standards of dress. These standards included, at a minimum, proper head-coverings, nicely made dresses in appropriate fabrics, and shoes if at all possible.

The popular Hollywood myth that Western women dispensed with corsets and hoops and wore cheap cotton ill-fitting dresses is just that - a myth. A Southern lady was a lady anywhere, and that included the West.